As part of my work to build a Matter controller using .Net, I find myself in need of mDNS again.

I dabbled with this a few years back and even managed to get something working with HomeKit on iOS. However, for my work with Matter, I find myself looking at my old code again! I thought it would be useful to try and resurrect this code and get it working with IPv6.

The Matter Smart Home protocol uses IPv6. DNS-SD and mDNS during its discovery and commissioning.

A Matter device will advertise its presence on a network using DNS-SD. Commissioners and controllers use DNS-SD to find them.

mDNS

mDNS is short for Multicast Domain Name Service. From what I understand, it works in almost the same way as the DNS your browser uses, except instead of central DNS server, it broadcasts requests onto the network. Essentially, it sends a Question and anything that can answer, will.

It leverages IP multicast, which is a special IP mechanism for propagating messages across an entire network, rather than from point to point.

In basic terms, to build an mDNS server, you open post 5353 and listen for multicast messages on 224.0.0.251.

DNS-SD

DNS-SD is a special use of DNS and the SD stands for Service Discovery. It’s a way to find all the services available on a network.

To make it work, you send a Question via mDNS. The Question has the name “_services._dns-sd._udp.local”. You then Answer this Question with a list of services, like http.

If the person asking the questions is interested in the particular service, they ask another Question, this time requesting more information. The Answer might include an IP address and a port, so the service can be accessed.

Upgrading my code

My first pass at mDNS was horrible https://github.com/tomasmcguinness/dotnet-mdns. Everything was hardcoded and it answered *every* query. This obviously needed to change if I wanted it to be little more usable.

Supporting IPv6

My original code, , was build for IPv4 and answered with HomeKit Accessory Protocol (HAP) messages. I need to upgrade it to work on IPv6 and send register Matter messages. I bet Apple are pretty mad their own HAP is being replaced 🙂

IPAddress multicastAddress = IPAddress.Parse("FF02::FB");

IPEndPoint multicastEndpoint = new IPEndPoint(multicastAddress, 5353);

EndPoint localEndpoint = new IPEndPoint(IPAddress.IPv6Any, 5353);

EndPoint senderRemote = new IPEndPoint(IPAddress.IPv6Any, 0);The bulk of the changes where things like IPAddress.Any to IPAddress.IPv6Any. I also changed the multicast address to FF02::FB, which is an IPv6 address.

using var socket = new Socket(AddressFamily.InterNetworkV6, SocketType.Dgram, ProtocolType.Udp);

socket.SetSocketOption(SocketOptionLevel.Socket, SocketOptionName.ReuseAddress, true);

socket.SetSocketOption(SocketOptionLevel.IPv6, SocketOptionName.MulticastInterface, true);

socket.Bind(localEndpoint);

socket.SetSocketOption(SocketOptionLevel.IPv6, SocketOptionName.AddMembership, new IPv6MulticastOption(multicastAddress));That was all it took to get my code up and running.

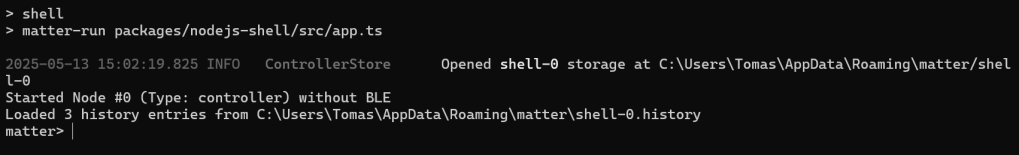

To test it, I fired up matter.js, launching a shell. From the matter.js directly, run this

npm run shell

Once the shell launches, run this command:

discover commissionableMy mDNS Console app started spitting out data, meaning it has received something over the mDNS port.

Returning something useful

Whilst my code was responding to a query, the response wasn’t being picked up by the matter.js shell.

To help me figure out what it should be returning, I did this: I launched another matter.js instance, this time one acting as a matter device.

npm run matter-deviceThis started broadcasting itself as a commissionable device. The matter.js shell found it

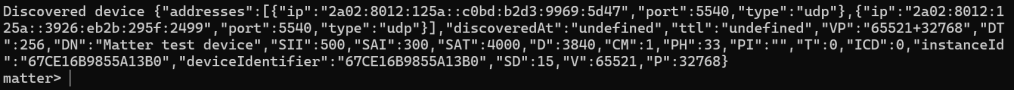

The Discovery app on my iPhone even found it.

I set about trying to replicate this.

First, I felt it necessary to at least understand the *shape* of the payloads I was sending and receiving. When I got my HAP code working, I simply copied and tweaked other payloads I was seeing. This time, I decided to be a little bit more thorough.

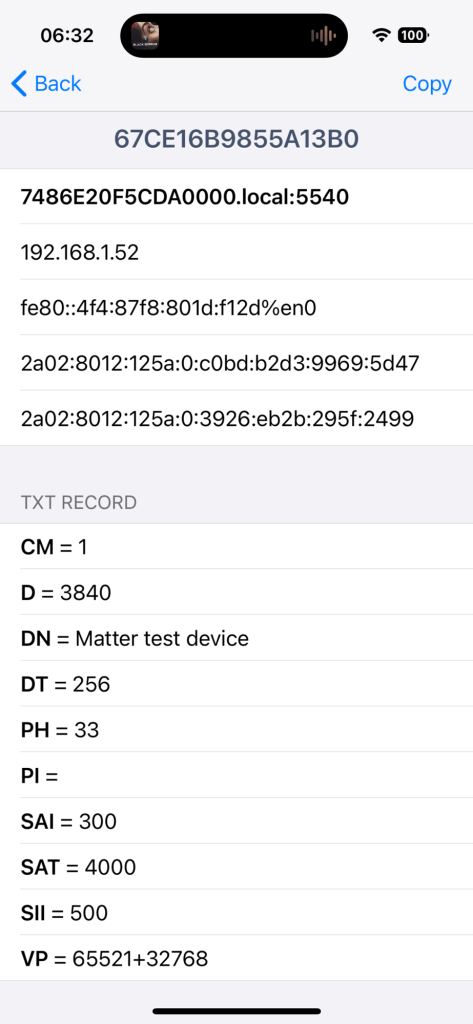

https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc6195 as the starting place. I do love a good RFC. On page 3, it gave me an outline of what the query is made up of.

First thing we’re interested in, whether or not the message is a Query or a Response. This is indicated by the QR bit of the flag bytes (QR, OpCode etc). We’re only interested in Queries at this stage.

var flags = contentSpan.Slice(2, 1);

var queryResponseBit = flags[0] >> 7;

var queryResponseStatus = queryResponseBit == 0x00 ? "Query" : "Response";We now know if the mDNS message is a query or a response.

Since we’re only replying, we can just ignore any and all responses.

Handing Queries

As I mentioned at the start, Matter uses DNS-SD with mDNS. mDNS covers how the DNS messages get passed around (using IP multicast).

My basic code just answered every question with the same set of records. On reflection, this was probably pretty confusing for anything else making mDNS requests on my network 🤣. I was ignoring anything that wasn’t a query, but answering *all* queries. To improve this, I needed to parse the incoming DNS payload and see what was being asked!

First, I created a new class to represent the DNS Request. This would encapsulate the parsing and present it in a structure. I moved some of my code in and cleaned it up.

var request = new DNSMessage(content);I could then easily pass the byte[] into it and get the full DNS message. However, when running this, I quickly found my parsing wasn’t as good as I thought! I kept reading beyond the bounds of the data.

One request came in and my code threw an exception!

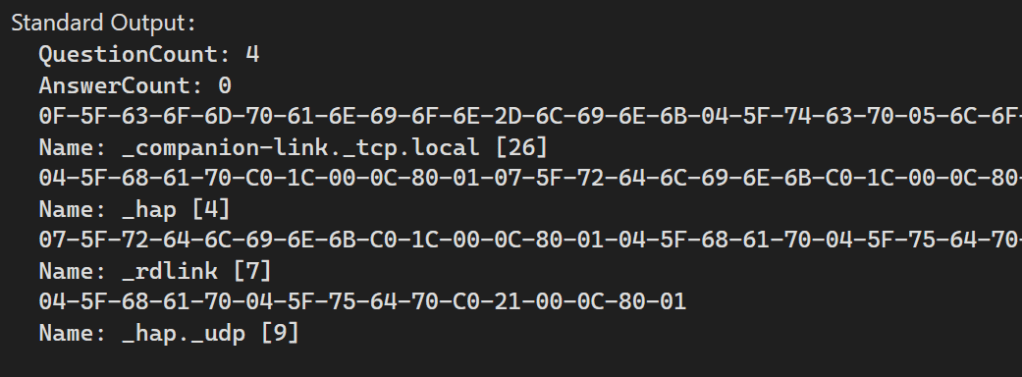

System.ArgumentOutOfRangeException : Specified argument was out of the range of valid values.I took the payload and created a unit test. Running it yielded this output before the exception was thrown

The names like rdlink�� and hap�_udp�!� didn’t look good!!

What’s in a name?

During my initial development all those years ago, I remember being surprised that the various DNS names aren’t just strings e.g. _hap._tcp.local. They actually have a special encoding.

Take _companion-link._tcp.local. This will come as a byte[]. The encoding breaks the name around the periods. This gives us three parts. Each part will start with a byte that gives us the length of the part. The byte[] is then null terminated.

0F-5F-63-6F-6D-70-61-6E-69-6F-6E-2D-6C-69-6E-6B-04-5F-74-63-70-05-6C-6F-63-61-6C-00The first byte, 0x0F, means we read 15 characters. This gives us _compananion. Then we get to 0x04 and that gives us _tcp, before we hit 0x05, which yields 6C-6F-63-61-6C and that converts to local. The final byte 0x00 is a null terminator, which means the string is finished.

So what’s the problem? Well, it turns out to be a little more complicated than that.

Let’s take a full request that I captured off the wire.

00-00-00-00-04-00-00-00-00-00-00-00-0F-5F-63-6F-6D-70-61-6E-69-6F-6E-2D-6C-69-6E-6B-04-5F-74-63-70-05-6C-6F-63-61-6C-00-00-0C-80-01-04-5F-68-61-70-C0-1C-00-0C-80-01-07-5F-72-64-6C-69-6E-6B-C0-1C-00-0C-80-01-04-5F-68-61-70-04-5F-75-64-70-C0-21-00-0C-80-01I’ll gloss over some of the details at this time. First thing to look at is 04-00. This tells us there are 4 questions. The next 6 bytes are null. These represent other counts. Look at the diagram above for help.

If you look closely, you’ll see the byte starting 0F-5F-63 bytes that make up the _companion-link._tcp.local are in bold. After the null terminator, 0x00, there are two 16bit numbers, 00-0C-80-01. These represented the type of record and the class of the record. We’ll look at that later. Immediately after you’ll see another array of bytes: 04-5F-68-61-70-C0-1C-00-0C-80-01. These are the next question.

The first by 0x04 is the length, and the next four bytes give us _hap. Then things change. The next byte is 0xC0, which would be a length of 192. This is longer than the 63 bytes allowed for a name!

As it turns out 0xC0 has special meaning! It’s a space saving mechanism. It’s hard to imagine needing to save a few bytes, but back in 1983, every byte counted.

C0 is a byte that indicates we are going to reuse part of another name somewhere else in the payload. The byte following the C0 contains an offset value. This offset points to another byte in the overall message payload.

We can see that the 2nd byte in this case is 1C. This is 28 in decimal. This means we look into the payload to the 28th byte. This points to the bytes 04-5F-74-63-70-05-6C-6F-63-61-6C-00 …, which you’ll recall from the first name will give us _tcp.local. This is part of the _companion-link._tcp.local name.

The full name is then _hap._tcp.local. Clever. It’s still amazing to me that over forty years later, DNS is still working. Imagine a Javascript framework being around that long, unchanged and still used?

I added a small tweak and the crash went away

A little more tweaking and a sort of recursive call to DecodeName and this was the result:

Four perfectly formed names!

We had our queries, we now had to answer them.

Answering the Queries

Answering a Query is a case of sending a DNS Message back to the machine that asked the question. It’s really that direct.

As this post is about the DNS-SD a special query is used, and its name is _services._dns-sd._udp.local. When we receive this, we need to answer with all the services we offer. For Matter, I’ll be returning one answer: _matter._udp.local. This name indicates we’re a Matter device on the network. It’s used by Matter Controllers to find devices dynamically, rather than relying on static IP Addresses.

To send this answer, we need to build up a DNSMessage that will contain the answer. If we get a query for _services, we add the answer.

var responseMessage = new DNSMessage(false);

if (request.Queries.Any(q => q.Name == "_services._dns-sd._udp.local"))

{

responseMessage.AddAnswer("_services._dns-sd._udp.local", RecordType.PTR, RecordClass.Internet, "_matter._udp.local");

}This approach was enough to get the code working, but obviously a little too hard-coded to be very reusable!

There is also tonnes of information missing here, like the IP address of where the services is.

I’ll come back to how I tackled this later on.

Asking the Questions

To resolve a query, it’s just a case of including some Records in the Query section of the DNSMessage and sending it out.

As the UDP socket is receiving a constant messages, the biggest issue is knowing when you’ve been answered!

I’m not sure there is an exact science to this, but my code just looks through the answers and if the answer contains one of my questions, I’ll assume it’s a match.

Responding to a Matter Query

As my short term goal is to advertise both nodes requiring commissioning and nodes that are operational i.e. have been commissioned already.

I’m interested in operational nodes right (as I want my controller to reconnect after it restarts), so I’ll be responding to the _matter._tcp.local service requests.

In my Program.cs console app, I simulate this like so:

UdpClient receivingUdpClient = new UdpClient(11000);

await service.Perform(new Advertising(new ServiceDetails("_matter._tcp.local", "TOMAS", 11000, addresses.ToArray())));This basically says advertise the service _matter._tcp.local on a host called TOMAS. It’s available on PORT 11000 on these IP addresses

The addresses I found using this

foreach (NetworkInterface ni in NetworkInterface.GetAllNetworkInterfaces())

{

if (ni.NetworkInterfaceType == ni.NetworkInterfaceType == NetworkInterfaceType.Ethernet)

{

if (ni.OperationalStatus != OperationalStatus.Up) continue;

foreach (UnicastIPAddressInformation ip in ni.GetIPProperties().UnicastAddresses)

{

if (ip.Address.AddressFamily == AddressFamily.InterNetwork)

{

addresses.Add(ip.Address.ToString());

}

}

}

}For simplicity I’m only doing IPv4. I still have to understand how to find usable IP addresses.

When answering the query for the _services._dns-sd._udp.local, the code replies using an Answer and a bunch of AdditionalInformation records

First, it replies with the service, _matter._tcp.local

response.Answers.AddPointer("_services._dns-sd._udp.local", service.Key);Then it adds a bunch of additional information

response.AdditionalInformation.AddPointer("_matter._tcp.local", serviceName);

response.AdditionalInformation.AddService(serviceName, 0, 0, service.Value.Port, hostName);

values = new Dictionary<string, string>();

values.Add("CM", "1");

values.Add("D", "3840");

values.Add("DN", "C# mDNS Test");

response.AdditionalInformation.AddText(serviceName, values);

foreach (var record_address in service.Value.Addresses)

{

response.AdditionalInformation.AddARecord(hostName, record_address);

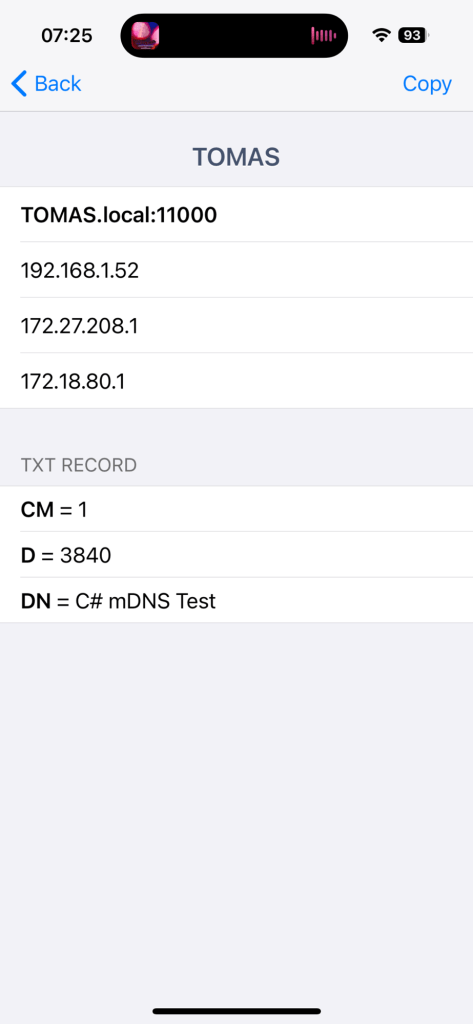

}I start the console app and open the Discovery app on my iPhone.

These are all the services available on my network. You can see _matter._tcp around the middle. If I open that, I can see my service, TOMAS

The two other devices listed (with proper names!) are Matter devices on my network.

Tapping TOMAS opens the details of the service.

You can see some IPv4 addresses, the port 11000 and a TXT record values I included.

Summary

With a basic working implementation or both discovery and advertising, I have enough to continue on my Matter Journey! The code is not particularly elegant or efficient, but it’s enough for me right now.

I’ve learned a tremendous amount about DNS and mDNS, which was one of the goals of this exercise.

If you want to see the code, it’s all up on Github at https://github.com/tomasmcguinness/dotnet-mdns

Leave a comment